Ceasefire 2005-2025: Twenty Years of Battles for Human Rights

The major exhibition in Bologna dedicated to my work over the past twenty years on human rights has just come to a close. It was an important exhibition—one that came from the heart.

Hosted in the prestigious Palazzo d’Accursio, overlooking Piazza Maggiore, it brought together all the organizations that have collaborated with me over the years on various human rights campaigns.

"Ceasefire 2005-2025: Twenty Years of Battles for Human Rights", curated by Lorenzo Balbi, celebrated more than twenty years of art as testimony and activism. With a direct and distinctive line, drawing has become a tool for civil resistance—giving a face and a voice to the fight for human rights, social injustice, and stories too often forgotten.

Set in the evocative Sala Ercole, the exhibition retraced some of the most emblematic campaigns of my journey: from the now-iconic portrait of Patrick Zaki, which became a symbol of international mobilization, to my work with PEN International on imprisoned journalists in Eritrea, and the illustrations created for the “Woman, Life, Freedom” campaign in support of protests in Iran.

My works have accompanied numerous Amnesty International campaigns, helping raise public awareness about human rights violations around the world. A section of the exhibition was also dedicated to the Mediterranean migration crisis, featuring pieces displayed aboard the Ocean Viking rescue ship by SOS Méditerranée. Another powerful section honored journalists killed in Gaza since October 7, 2023—a project developed in collaboration with the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) in New York.

Below are the texts displayed during the exhibition, which describe and explore each of the sections in depth.

Photographs by Michele Lapini.

GIANLUCA COSTANTINI: DRAWING AS TESTIMONY

Text by Lorenzo Balbi

The exhibition dedicated to Gianluca Costantini celebrates more than twenty years of an art form that becomes both testimony and activism. Through the incisive line of his illustrations, Costantini has transformed drawing into a tool for civil resistance—giving face and voice to human rights struggles, social injustices, and stories too often forgotten.

The exhibition traces his artistic commitment through the campaigns that have defined his journey. Among them, the one for Patrick Zaki stands out: the portrait of the Egyptian activist and researcher, created shortly after his arrest in 2020, became a symbol of the international mobilization for his release. The original artwork, now part of the collection at MAMbo – Museum of Modern Art of Bologna, is a powerful reminder of art’s ability to keep public attention alive.

Alongside this iconic piece, the exhibition presents other key moments in his activism: the series dedicated to journalists imprisoned in Eritrea, created in collaboration with PEN International; the portraits of victims of patriarchal violence, as tools of remembrance and denunciation; and the images for the “Woman, Life, Freedom” campaign, born after the death of Mahsa Amini in Iran and turned into symbols of protest against the regime. His distinctive line has also accompanied the fight for freedom of information, with works dedicated to Julian Assange and WikiLeaks, and his most recent pieces include portraits of journalists killed in Gaza, made in collaboration with the Committee to Protect Journalists.

The exhibition’s key image and title refer to Palestine—specifically to Rahaf Ziad Abu Suweirh, a young Palestinian girl who died of a heart attack after a bombing. With the delicacy of his line, the artist conveys both the fragility and the horror of war, turning a personal tragedy into a universal symbol of grief and resistance. Rahaf’s face becomes a silent warning, an invitation to reflect on injustice and the devastating impact of conflict on the most vulnerable.

Equally powerful are the works addressing the migration crisis in the Mediterranean. The exhibition includes illustrations shown aboard the Ocean Viking rescue ship operated by SOS Méditerranée, which have brought visibility to the ongoing tragedy faced by people fleeing across the sea.

Gianluca Costantini is not only an illustrator but an activist who uses drawing as a peaceful yet powerful weapon. His works, shared across the globe and often at the center of political controversy, prove that art can be action, resistance, and memory. This exhibition is a journey through his tireless pursuit of truth and justice—a testimony to how images can become a collective cry for freedom.

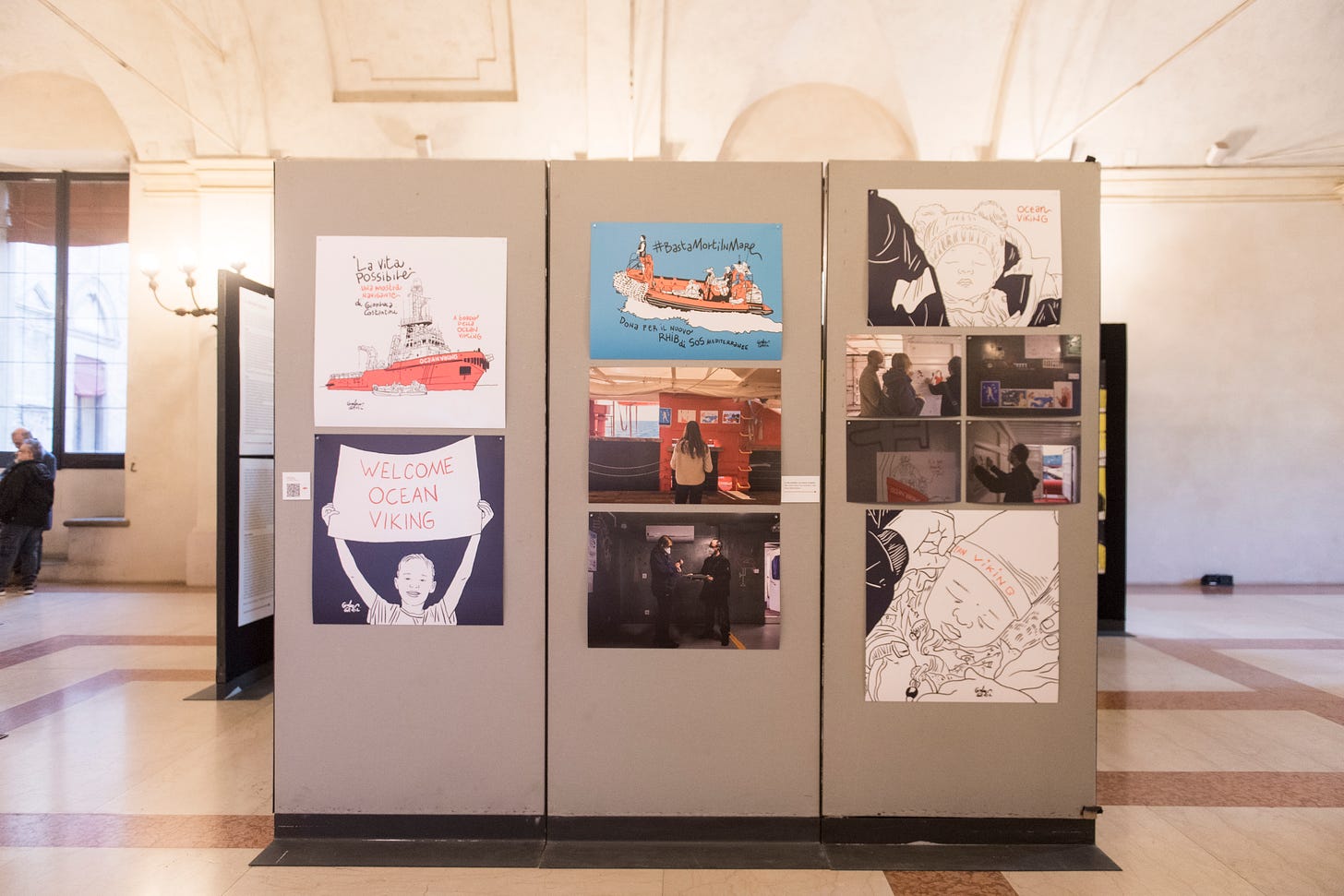

The Possible Life: A Traveling Exhibition on the Ocean Viking

In the darkness of a night on the open sea, a still bundle on an overcrowded rubber boat looked like nothing more than a pile of abandoned clothes. But it was Abdou, a newborn just eighteen days old, who had survived a week-long crossing. His rescue aboard the Ocean Viking—marked by the rescuers’ uncertainty and hope—became a symbol of all the suspended lives crossing the Mediterranean.

Inaugurated aboard the Ocean Viking in January 2023, this traveling exhibition transformed the ship’s spaces—from the deck to the clinic, and even the shelter for women and children—into a floating gallery. Costantini’s drawings, with their bold lines moving between denunciation and hope, accompanied the daily work of the SOS MEDITERRANEE crew in the central Mediterranean.

Through his art, the artist gives form to stories that risk remaining unseen, turning drawing into a testimony of the universal right to life and dignity. The Possible Life thus becomes a collective journey beyond the sea’s horizon, where every life has the right to be saved.

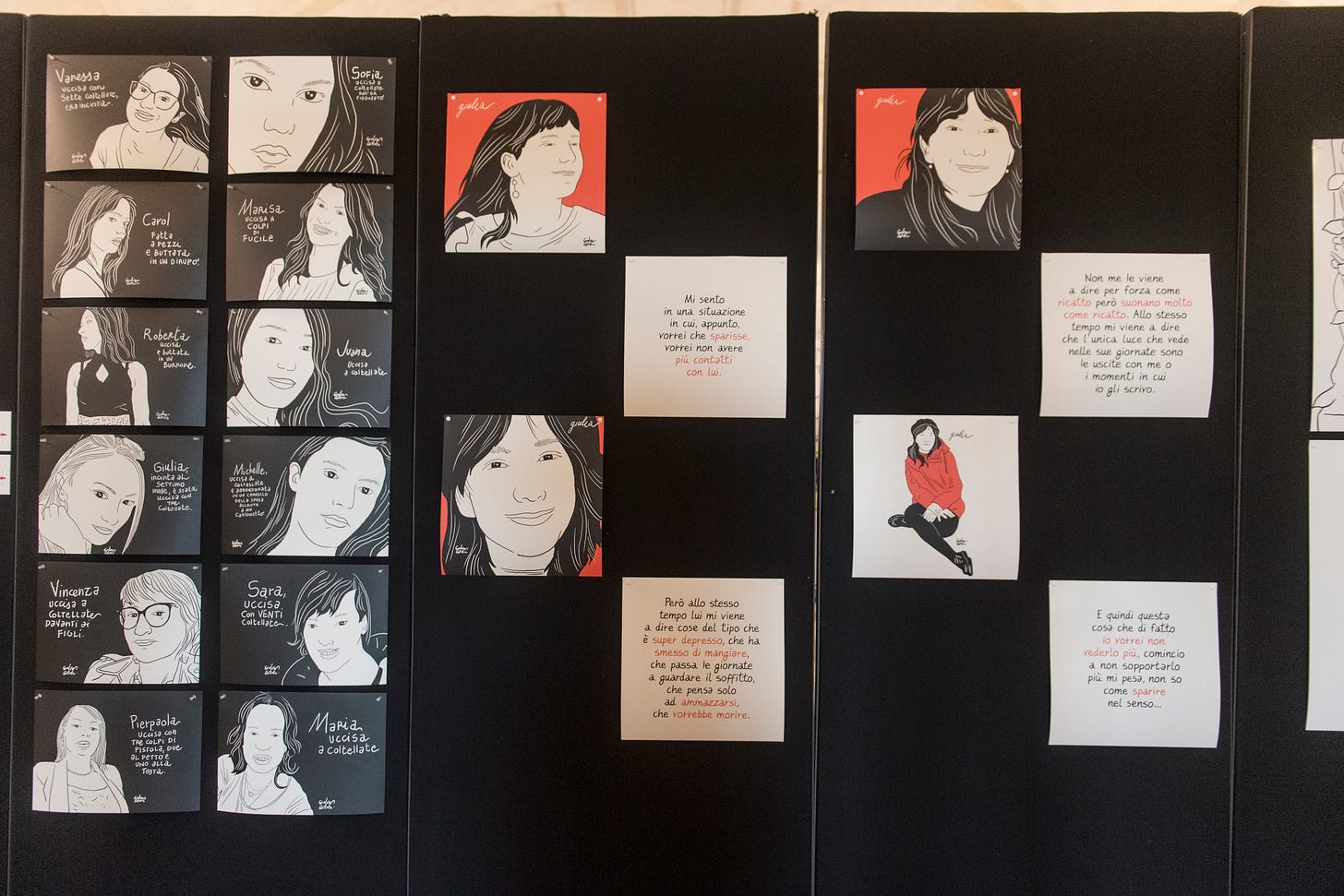

There Are Loves Without Paradise

Text by Elettra Stamboulis

Narrative journalism has long explored the shadows of human relationships, giving voice to the crimes that emerge from the hidden folds of everyday life. Yet often, these events remain shrouded in anonymity—compressed into a headline of crime reporting, stripped of a face and a name. Gianluca Costantini, illustrator and activist, confronts this invisibility with a body of work that restores dignity to the victims of patriarchal violence, offering them a face, a space, a memory.

"Feminicide", a word that speaks of an ancient injustice, is not just a term: it is an act of linguistic and cultural honesty. It means naming a specific, brutal reality—the killing of a woman simply because she is a woman. It is a way of becoming the “fertile leaven” of future human relationships, allowing awareness to take root and breaking the silence of complicity.

For Costantini, drawing the faces of the victims is a moral obligation. Each portrait becomes an island of interrupted life, a fragment of an emotional atlas that demands remembrance. Drawing is not merely an aesthetic gesture—it is a political act, a way to transform individual pain into collective memory. The artist creates a "participatory geography" that draws the viewer into a process of re-membering, in the literal sense of “bringing back to the heart.”

Costantini asks us to look at these faces, to carry them with us, not to look away. Because remembering is the first step toward change—and each face is a testimony that speaks to us, to our present, and to the possibilities of a different future.

The Shield of the Line for Patrick Zaki

Gianluca Costantini used his drawings as a powerful tool to raise awareness for the cause of Patrick Zaki. During Zaki’s detention in Egypt (2020–2023), Costantini created numerous illustrations that became iconic symbols of the campaign for his release.

His portrait of Patrick Zaki—rendered in black and white, showing the Egyptian student from the University of Bologna with his recognizable curly hair and determined gaze—quickly became a symbol of mobilization. The image was widely shared on social media, displayed at public demonstrations, and projected onto buildings in several Italian cities, especially in Bologna.

Throughout Zaki’s imprisonment, Costantini continued to produce illustrations that visually documented the key moments of the case, helping to keep media attention focused on the situation. His work played a vital role in sustaining public engagement and pressure for Zaki’s release, showing how art can serve as a powerful instrument for activism and human rights advocacy.

Costantini’s artistic commitment extended beyond individual illustrations; he also took part in initiatives, exhibitions, and events dedicated to Zaki’s cause. In doing so, he helped construct a visual narrative that kept public awareness and solidarity alive throughout the duration of the campaign.

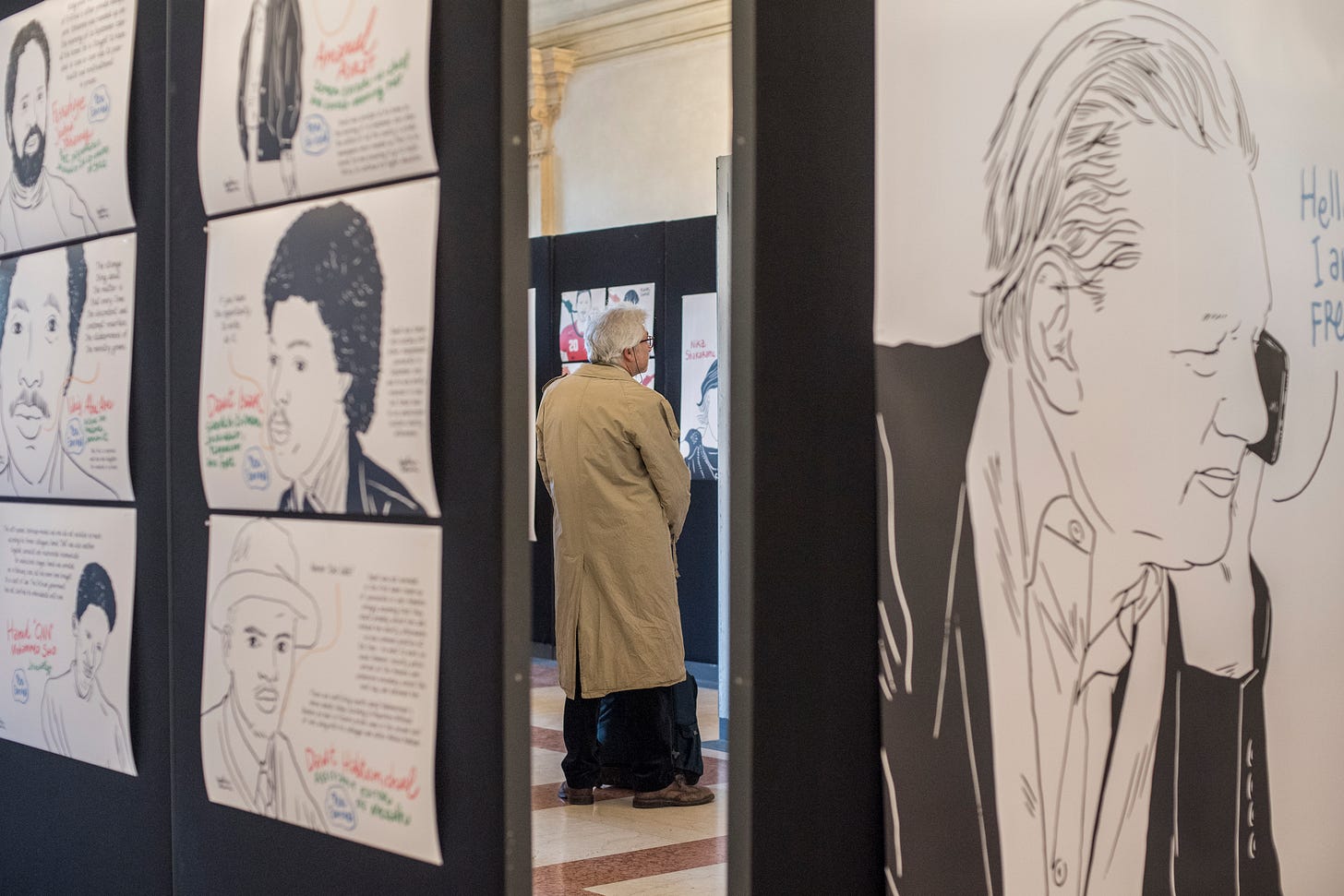

In the Crosshairs of Memory

Following the Hamas attack of October 7, 2023, and the subsequent Israeli retaliation, Gianluca Costantini began a visual documentation project, portraying journalists killed in the Gaza Strip. In close collaboration with the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) in New York, the artist has created a growing memorial that expands day by day.

Costantini, an internationally renowned artist and political activist, is known for his commitment to giving a face and iconic presence to the victims of injustice. This project does not aim to compensate for the losses—an impossible task—but instead acts as a votive offering, a gesture of remembrance for those who made documentation their life’s mission.

These portraits have already taken on a life of their own in protest movements from Atlanta to New York, Berlin to Seattle, and even Naples. Like many of the artist’s works, these drawings become tools of communication in the hands of citizens who, from distant parts of the world, mobilize to demand truth, justice, and a ceasefire.

Portraying those who stand behind the lens—a task not to be taken for granted given the often private nature of journalists—becomes a profound gesture of gratitude, a collective ritual of mourning and atonement, an attempt to preserve the memory of people who, though never known personally, have become dear to us.

The numbers of this tragedy (as of January 10, 2025):

160 journalists killed in the conflict (152 Palestinians, 2 Israelis, 6 Lebanese)

49 journalists injured

2 journalists missing

75 journalists arrested

Additionally, there have been reports of assaults, threats, cyberattacks, censorship, and intimidation through the targeting of family members.

The systematic elimination of media in Palestinian territories, especially in the Gaza Strip, raises a crucial question: how will we ever know the truth about these months of violence if those tasked with documenting it are physically eradicated?

The Forgotten Journalists of Eritrea

In 2019, Gianluca Costantini collaborated with PEN Eritrea to give voice to a forgotten story: that of the imprisoned Eritrean journalists. Through 15 drawings, Costantini transformed silence into visual testimony, creating essential yet profoundly evocative portraits of these information professionals deprived of their freedom.

Costantini approached this series with particular sensitivity and attention. Despite the scarcity of available photographic material—often limited to old, low-quality images—the artist carefully studied Eritrean facial features, translating them into simple yet precise lines, where each stroke tells a story of resistance.

Among the most touching portraits is that of Amanuel Asrat, whose poetic words deeply moved the artist, and that of Dawit Isaak, emblematic figures of a broader human tragedy. Each illustration is accompanied by carefully selected quotes that amplify the silenced voices of these journalists.

The digital technique chosen for this series preserves the artist's calligraphic simplicity, allowing each portrait to be created in approximately 30 minutes. The project was made possible through collaboration with Eritrean journalist Abraham T. Zere.

Social Drawing

Text by Gianluca Costantini

It’s morning, with its blue stamped up high, and my eyes that won't open, after a peaceful night of hazy dreams. The light always sneaks in through the windows and whitens the walls of my house as if it wants to clean them. I move around the house, having breakfast while a dog stares at me from the couch. There is never anyone in the house in the morning; everything is still, and my provincial city is serene. Not far from here, it is not the same, and I always feel connected to the unstable world: but it hasn’t always been this way.

BEFORE I grew up in a family with very modest economic conditions, without any political, intellectual, or artistic education. Although it’s cliché to say, art saved me. Around the age of seventeen, art became an obsession, wanting to be part of it became a well-defined and selfishly driven goal; it still is. All the unconscious traumas I had suffered in my childhood were healed by the poems of Rimbaud, anesthetized by the drawings of Klimt, and cured by the films of Greenaway. I made new fathers, older cartoonists, and Academy teachers, and I began taking trains to Italian cities. During the early years of the Academy, I established a close relationship with artists and magazines, starting to publish at a very young age. My world was very aesthetic, decorative, full of dreamlike beauty, constantly traveling to escape reality. But little by little, this world cracked, and within me grew a dissatisfaction. Roberto Daolio, an art critic who followed me with interest, once asked me, "Is something wrong?" He had sensed my discomfort; I was stuck, stranded, stranded.

AFTER Then came Sarajevo, in 2001, with its walls pierced by bullets, with its vast cemetery on the hill, with the map for mines. I had been sent by GAI (Young Italian Artists) to the Mediterranean Biennale. The war had just ended, and I had never been in a war zone. Everything changed here. I wandered the streets of the city for days, ignoring the Biennale appointments and my traveling companions. Everything struck me—the glances, the children, the people living in houses without walls, where you could see their daily intimacy.

I came back home with a heavy emotional baggage, and the following month I left for Istanbul. I had changed, and I had to see the world I was drawing. A few years later, I began organizing events with Elettra Stamboulis in Ravenna, my city. We started with Joe Sacco, the famous Maltese cartoonist, and continued with Aleksandar Zograf and Marjane Satrapi. We didn’t stop for more than fifteen years organizing and, most importantly, getting to know each other. These authors, a few years older than me, unknowingly instilled new ideas and energy in me. One day, by chance, I flipped through a book by the German photographer Ernst Friedrich, "War Against War," a photographic book with short captions shedding light on the consequences of World War I, intending to show the true face of war (wounded, mutilated, executions, suffering, misery, and death). This book gave me the idea to create political drawings with text on them, and to do so, I completely changed my drawing style, abandoning everything I had done in the previous ten years.

I titled the first series "el indio." It was about twenty drawings depicting small events in Palestine, Iran, the Philippines, and Afghanistan, which I published on a web page. I also sent them to the Indymedia portal, and some of them were translated into various languages. The drawings worked; I received emails of thanks or requests for permission to publish them. Social networks didn’t exist yet, and email and forums were the only means of sharing.

In 2006, I joined Twitter, began posting my drawings in English, even though I don’t know the language because I suffer from dyslexia, which made it impossible for me to learn it. During an interview with a journalist from Pen America, I told him I didn’t know English. He was surprised and said maybe that’s why my images and my texts in English were so direct—they were constrained by the simplicity of the words I had to use, and that’s why they reached people so directly.

The Twitter community following my profile grew more and more, but it was not a mainstream profile; it was a profile that brought together people who did, spoke, or lived the issues I drew. This strange feedback loop made the drawings go viral, sometimes exponentially. Now, after sixteen years of using Twitter, I can say I’ve created a small T.A.Z. (Temporary Autonomous Zone), where people help each other, and I do my part with drawing. Almost every day for many years, I draw people whose freedom of movement or expression is taken away, people who are unjustly killed or who disappear.

Every week I receive messages and letters from parents or friends of these people asking me to make a drawing because it could help spread the news. The drawings are archived on my website, www.channeldraw.org, which has now become a small information portal created only with drawings, a database that is constantly raided, completely free of copyright.

HOW IT WORKS Over the years, I have deepened my historical and political knowledge of several countries I try to follow the news of every day—Turkey, Egypt, Bahrain, China, Belarus, Libya, Eritrea, Saudi Arabia, and Palestine. These are countries where human rights are a crime, where tolerance is not allowed. I am in contact with many activists and journalists who work and live in these countries, with whom I have an ongoing exchange of information and photos. Messages constantly arrive about abuses and arrests, and I try to keep up by drawing as many cases as possible, helping as many people as I can. It’s an unpaid job, but it is done as an artistic action, as an artwork in motion that never ends. I make the drawings in a few minutes, adding small texts, then I prepare the tweet, directing it to people I know are interested in the case. When I press the send button, the drawing begins its life and enters the lives of other people, often showing up in the hands of people in places thousands of kilometers away. The moment it happens, I know the drawing is doing its job and is subtly changing the course of that story. My goal is to be present in distant stories, to be part of real events happening somewhere in the world, and above all, to send a message of love to these people.

A message that says, "We don’t know each other, but I am here to help you."

This also happened in the well-known case of Egyptian student Patrick Zaki. On February 7, 2021, an anonymous Egyptian activist, with whom I have been in contact for many years, informed me that a young Egyptian man from Bologna had disappeared inside Cairo Airport. I created and published the drawing immediately; it was adopted by everyone in Italy and became the most iconic image of the large campaign for Patrick’s release. This is what I do. I am a free artist, drawing for those who can no longer express their freedom.

By Gianluca Costantini, published in Human Rights Portraits, Becco Giallo, 2023.

Woman, Life, Freedom

In September 2022, the face of Mahsa Amini became the symbol of a revolution. Her death in the custody of the Iranian morality police sparked an unprecedented wave of protests, mainly led by courageous women who defied a decade-long oppressive system.

Through his distinctive style, Gianluca Costantini captures this historic moment, beginning with a portrait of Mahsa. His drawing is not just a simple representation, but a powerful act of testimony: the face of the young Kurdish woman emerges from the page as an icon of peaceful resistance, her features drawn with a simplicity that amplifies its emotional power.

The essential lines of the drawing tell a broader story: that of a generation of Iranians who found in the protest "Woman, Life, Freedom" the voice to claim their fundamental rights. Mahsa's portrait thus becomes the starting point for a visual narrative that extends through the streets of Tehran, Isfahan, Shiraz, and beyond, documenting a struggle that continues to this day.

The drawings have found space in numerous squares around the world and have been exhibited in prestigious international cultural institutions. In the United States, they reached Portland University and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. In Estonia, they were welcomed by Tallinn University, while in France, they have graced the most important exhibition spaces in Paris: the Museum of Modern Art Palais de Tokyo, the Academy of Fine Arts, the Georges Pompidou Centre, and the Palais de la Porte Dorée. In Italy, the Sigismondo Castromediano Museum in Lecce included them in its collection.

The resonance of the work has also reached the world of cinema, with director Jane Campion walking the red carpet at the Venice Film Festival carrying one of these drawings.

The impact of the initiative has extended to institutional buildings, with the facades of several municipal palaces becoming canvases for these drawings, including the historic Palazzo D'Accursio in Bologna.

Julian Assange. WikiLeaks and the Battle for Freedom of Information

Costantini’s graphic novel, with text by Dario Morgante, takes us through two decades of digital history — from Assange’s early forays into the hacking world to the revelations that forever changed the way we see power and truth. At the heart of the work is the 2010 video that documented the killing of Iraqi civilians, a turning point that marked the irreversible breakdown between WikiLeaks and international institutions.

With his distinctive style, Costantini doesn’t just illustrate a story: he transforms each panel into an act of testimony and resistance. His artwork recounts not only Assange’s legal ordeal — now imprisoned in the UK and facing possible extradition to the United States, where he risks up to 175 years in prison — but also the broader fight for freedom of information in the 21st century.

The exhibition is enriched by contributions from two authoritative voices: Riccardo Noury, spokesperson for Amnesty International Italy, who highlights the exceptional nature of a coalition of states mobilized against a single individual; and Sheila Newman, who places Assange within the context of our interconnected global era.

Originally published in 2011 by Becco Giallo and reissued in 2024 by Altreconomia.

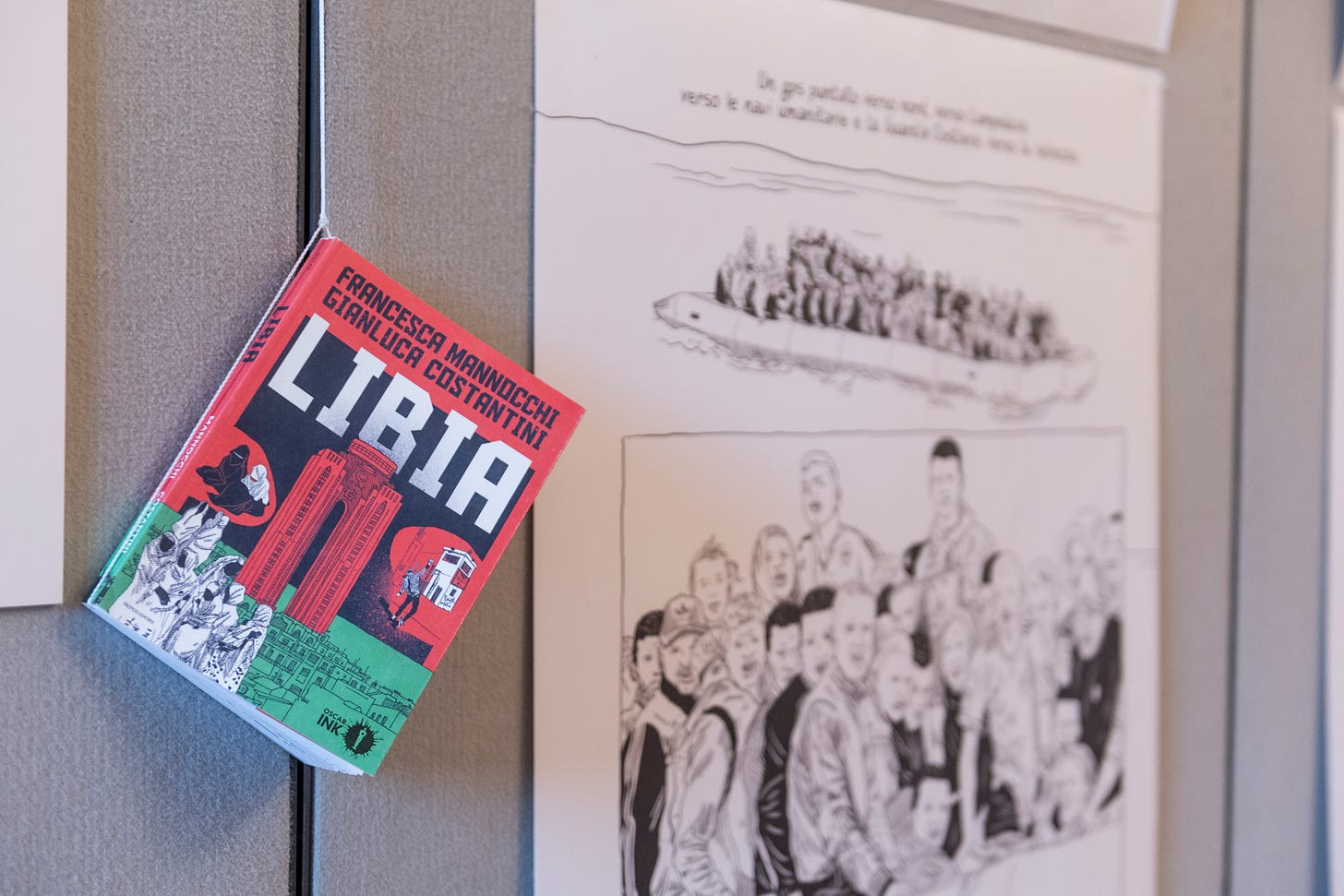

Libya

In Gianluca Costantini’s panels, accompanied by the words of Francesca Mannocchi, a Libya comes to life that escapes the media simplifications and the polarizations of the Italian public debate. A country that cannot be told through easy dichotomies: interventionists vs. pacifists, supporters of restrictive migration policies vs. human rights defenders.

Costantini’s visual narration takes us to the heart of a wounded nation, where daily life is marked by endless queues in front of banks to obtain devalued currency, where young people who once fought against Gaddafi now look back with bitter nostalgia, remembering a time when at least the essential services were not lacking: electricity, fuel, and economic stability.

The artist’s lines capture the essence of a population held hostage: mothers waiting for children who will never return, elderly people who carry the weight of decades of dictatorship in their eyes, ordinary citizens living in constant fear of kidnappings and abuses. The images stand as testimony to a complex reality, where violence is not just that of weapons but also the invisible violence of daily precariousness.

Costantini and Mannocchi present us with a portrait of a Libya different from the one we are used to seeing, a Libya that asks to be understood in its painful complexity.

A book published in 2019 by Mondadori, now in its fourth reprint in 2025.

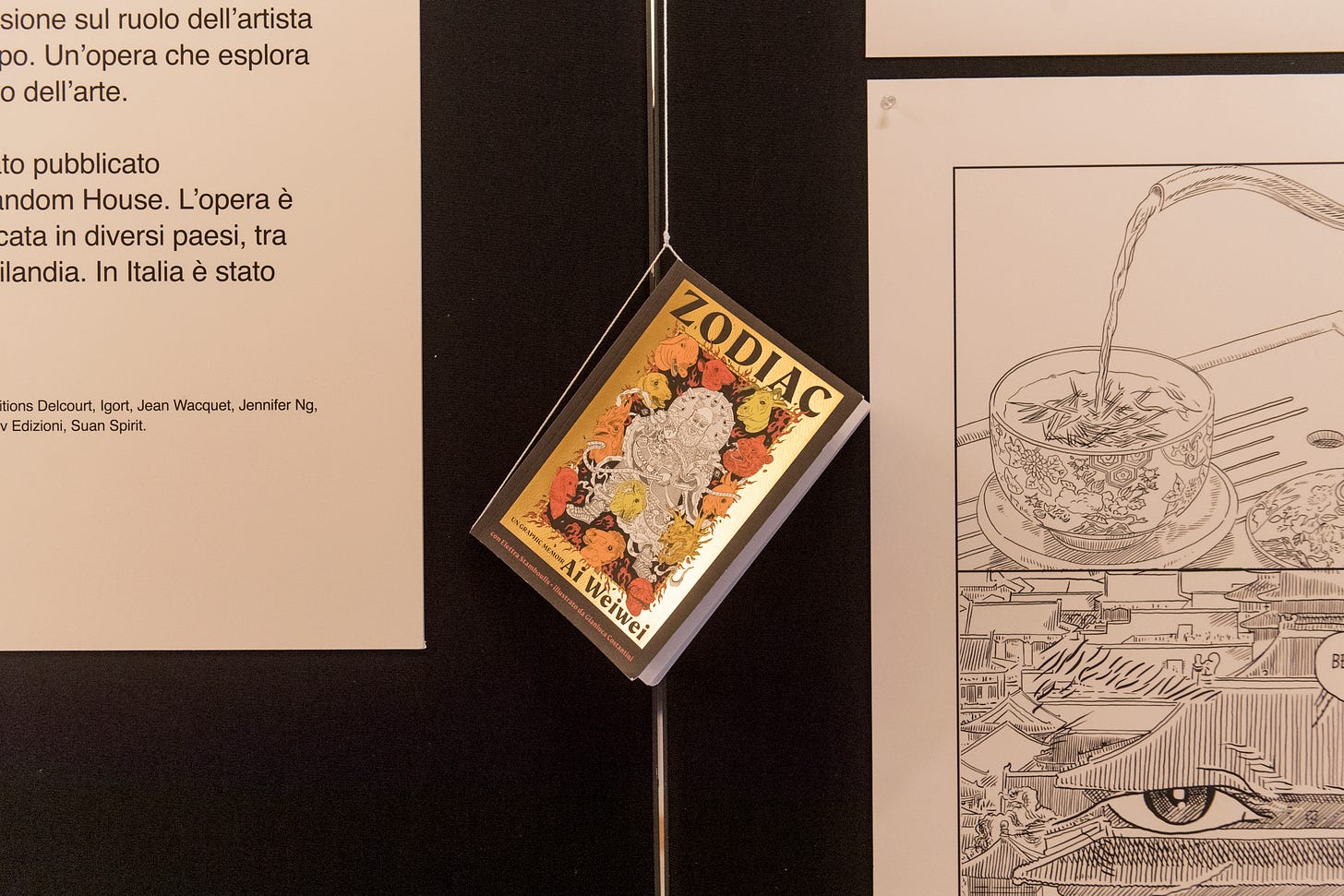

Zodiac

"Zodiac" represents a work that masterfully blends the tradition of the Chinese zodiac with the personal and political history of one of the most influential artists of our time. This graphic novel, born from the collaboration between the renowned artist and activist Ai Weiwei and illustrator Gianluca Costantini, with the screenplay by Elettra Stamboulis, offers a layered and deeply meaningful narrative.

The work uses the twelve signs of the Chinese horoscope as its narrative structure, recurring elements in Ai Weiwei's work, to weave a story that transcends a simple biography. Through this narrative device, the book explores three interconnected dimensions: the artist's personal history, the transformation of contemporary China, and a broader reflection on the role of art in society.

The narrative unfolds through crucial moments in Ai Weiwei’s life: from his childhood marked by his father’s exile, a dissident poet condemned to forced labor, to his formative years in the United States, and then his detention in Chinese prisons. The story does not follow a linear chronological order but moves freely through time, reflecting the workings of human memory and offering a deeper perspective on the complexity of lived experience.

Costantini’s illustrations create an effective bridge between Chinese folklore tradition and modernity, highlighting the socio-political tensions that permeate the entire narrative.

The work stands out for its ability to intertwine seemingly distant elements: the ancient tradition of the Chinese zodiac, the biographical events of a contemporary artist, and the analysis of political present. This intertwining creates a work that goes beyond a mere illustrated memoir, becoming a profound reflection on the role of the artist as a witness and critic of their time.

"Zodiac" thus emerges not only as the biography of an extraordinary artist but as a mirror through which to observe the complex dynamics between art, power, and resistance in the contemporary world. It is a work that speaks of identity, memory, and the transformative power of art, telling a personal story that becomes universal.

"Zodiac" is a graphic novel originally published in 2023 by Penguin Random House. The work has since been translated and published in several countries, including Portugal, France, Germany, and Thailand. In Italy, it was published by Oblomov Edizioni.

Art as Testimony: A Journey Through Comics and Activism

Gianluca Costantini’s artistic journey began on the streets of Ravenna, his hometown, where in 1987, at just sixteen, he took his first steps into the world of comics while studying at the Institute of Art for Mosaics. A pivotal encounter marked these early years: that with Vittorio Giardino, a master of Italian comics, who opened the doors of his studio in Bologna to Costantini, introducing him to a city that would become essential to his artistic path.

His time at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ravenna proved to be formative not only in terms of education but also for the influential figures he met—mentors who helped shape his artistic vision: Fabrizio Passarella, Carlo Branzaglia, Vittorio D’Augusta, and Dede Auregli. His first publication came in 1993 when Schizzo, the magazine of the Andrea Pazienza Center in Cremona, featured one of his comics, while the newspaper Il Manifesto began publishing his illustrations.

Throughout the 1990s, Costantini emerged as a prominent figure in the European underground scene. His work appeared in independent magazines such as Interzona in Italy, Stripburger in Slovenia, Babel in Greece, and Laikku in Finland. In 1997, art critic Roberto Daolio recognized his talent and curated his first exhibitions in the world of contemporary art. The following year, Bologna awarded him twice: he won both the Iceberg Young Artists competition and the prestigious Guercino Prize.

The new millennium brought a digital shift. In 2000, Costantini launched inguine.net, a pioneering project exploring web-based comic language, which later evolved into the magazine inguineMAH!gazine, published by Coniglio Editore. But 2001 marked a profound turning point in his artistic awareness, when he participated in the Biennale of the Mediterranean in Sarajevo. The city, still bearing the wounds of civil war, left an indelible mark on his artistic and political consciousness.

His social commitment deepened: he curated the Italian exhibitions of two giants of socially engaged comics—Joe Sacco in 2001 and Marjane Satrapi in 2003. In 2005, with Elettra Stamboulis, he founded the Komikazen Festival of Reality Comics, which he would direct for over a decade, until 2016.

From 2004 onward, his art increasingly became a direct testimony of global events. He collaborated with Indymedia to document protests and revolutions: from the Egyptian uprisings of 2011 to the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul in 2013, and the Hong Kong demonstrations of 2019–2020. His human rights activism intensified in 2014 when he began documenting the conditions of prisoners in countries such as Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, China, Turkey, and Egypt.

His artistic voice became increasingly uncomfortable for authoritarian regimes. In 2016, following the failed coup in Turkey, he was accused of terrorism and tried in absentia by the Turkish government for his drawings. Yet this did not deter him: in 2019, he collaborated with PEN International to expose human rights violations in Eritrea, while his work intersected with organizations such as Amnesty International, ActionAid, Arci, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) in New York, and SOS Méditerranée.

The year 2020 marked another significant chapter with the creation of the iconic image for the campaign to free Patrick Zaki. The illustration, drawn the same day the Egyptian activist was arrested, became a symbol of the human rights struggle, with installations in several Italian cities, including a monumental one at the Archiginnasio Library in Bologna.

His recent works reflect the international dimension his work has reached: he collaborated with Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei on Zodiac and with journalist Eric Meyer on Xi Jinping: The Emperor of Silence—works that confirm his ability to use the language of comics as a powerful tool of social critique and testimony.

Today, Gianluca Costantini stands as one of the most significant voices in the global landscape of politically engaged comics, where art and activism merge into a universal language that continues to narrate and denounce the injustices of our time.